Sortilin and EGFR nuclear interaction in EGF-stimulated cells

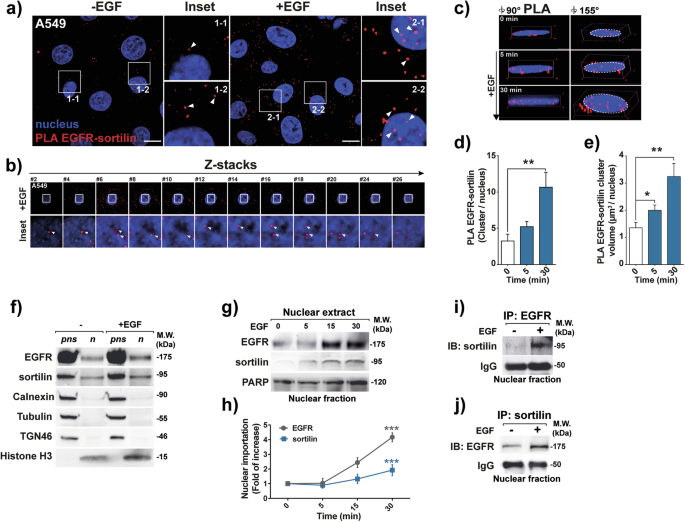

Based on findings showing that sortilin limits EGFR proliferative signaling [18, 19], we tested whether sortilin exhibits a tumor suppressor-like activity by acting on its nuclear signaling network. Although sortilin physically interacts with EGFR at or near the plasma membrane in A549 cells, as previously reported [18, 19], we also detected EGFR–sortilin complexes toward the nuclei of cancer cells, following EGF stimulation, as shown by red spots indicating sites of proximity ligation amplification (PLA) (Fig. 1a; insets 1.1 to 2.2). Z-stack confocal images and three-dimensional projections at 90° and 155° confirmed that EGFR–sortilin complexes localized within the nuclei of EGF-stimulated cells (Fig. 1b; insets showing z-axis #2 to #26, and Fig. 1c), ruling out artificial superposition of red spots in the 2D plan. After 5 min of EGF stimulation, both the number of EGFR–sortilin clusters and their total nuclear volume increased significantly (p < 0.05, Fig. 1c–e). This suggests that the translocation of EGFR–sortilin complexes begins early in the process of EGFR endocytosis.

Fig. 1: Sortilin and EGFR interact together in the nuclei of cancer cells.

a Proximity ligation assay (PLA) showing the interaction between sortilin and EGFR in the lung adenocarcinoma cell line A549 in the absence (-EGF) or presence of EGF (+ EGF, 50 ng/mL) for 30 min. Red spots indicate sites of PLA amplification, reflecting interactions between sortilin and EGFR. Scale bar, 10 μm; white arrows show EGFR–sortilin clusters. b Z-stack sections of confocal microscopy images showing sortilin and EGFR interactions in z-axis (insets #2–26). White arrows show EGFR–sortilin clusters. c 3D confocal microscopy images showing EGFR–sortilin interactions at angles of 90° and 155° following EGF stimulation (0, 5 and 30 min with 50 ng/mL EGF). d Quantification of EGFR–sortilin spots per nucleus, following 0, 5 and 30 min of EGF stimulation (50 ng/mL). e Estimated volumes of EGFR–sortilin clusters per nucleus (µm3/nucleus following 0, 5 and 30 min of EGF stimulation (50 ng/mL)). f A549 cells were stimulated with EGF (+ EGF, 50 ng/mL) for 30 min or not, control (–), before solubilization to proceed with subcellular fractionation. The nuclear extract (n) and post-nuclear supernatant (pns) were then subjected to western blotting with anti-EGFR, anti-sortilin, and a set of antibodies directed against the endoplasmic reticulum with anti-calnexin, the cytoskeleton with anti-tubulin, the trans Golgi network with anti-TGN46 and the nucleus with anti-histone H3 to rule out cytoplasmic contamination in nuclear fraction. g Immunoblots showing kinetics of EGFR and sortilin nuclear importation following EGF stimulation of A549 cells. Nuclear fractions were obtained at 0, 5, 15, and 30 min after stimulation with 50 ng/mL EGF, PARP protein levels were used as a loading control. h Quantification of nuclear importation of EGFR and sortilin following EGF stimulation were normalized on PARP expression in fold of control. Molecular weights (MW) are shown in kilodaltons (kDa). i, j Confirmation of EGFR–sortilin interactions by nuclear co-immunoprecipitation of A549 cell lysates in the absence, control (–), or presence of EGF (+, 50 ng/mL) for 30 min and immunoblotted (IB) respectively with anti-EGFR or anti-sortilin antibodies.

To validate these findings, we isolated nuclei and post-nuclear supernatant (pns) fractions and performed western blotting to assess protein expression. We used specific markers for Trans Golgi Network (TGN46), endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (calnexin), and cytoskeleton (tubulin) to exclude cytoplasmic contamination in the nuclear fraction. Histone H3, a chromatin packaging protein, was used as a marker for the nuclear fraction. Our analysis revealed both EGFR and sortilin expression in the nuclei of EGF-stimulated cells (Fig. f), with expression increasing significantly at 30 min (p < 0.001, Fig. 1g, h). These results corroborate confocal images, indicating translocation of EGFR and sortilin to the nuclei in response to EGF stimulation. Immunoprecipitation from isolated nuclei also demonstrated an increase in EGFR–sortilin complexes following EGF stimulation (Fig. 1i, j), further supporting the findings from PLA assay.

Role of EGFR and sortilin in nuclear translocation

In light of these results, we next examined the mutual role of EGFR and sortilin in their nuclear translocation. EGFR silencing significantly reduced the amount of sortilin in nuclear lysate, even after EGF stimulation (p < 0.05, Fig. 2a, c), suggesting that sortilin translocation is dependent on EGFR rather than another member of the EGF receptor family. Conversely, when the SORT1 gene encoding sortilin was depleted in A549 [18], EGFR nuclear translocation was not impaired; in fact, it increased significantly (#, p < 0.05, Fig. 2b, d, e). However, because EGFR remains largely retained at the plasma membrane in SORT1-depleted cells [18] (Fig. 2b), the amount of EGFR in the nucleus was significantly lower than in the empty vector control pLKO (p < 0.01, Fig. 2d). Hence, to further investigate the respective roles of EGFR and sortilin in nuclear translocation, we engineered HEK293T knockout cells for either EGFR or SORT1 depletion by using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene silencing (Figs. 2f–k). The HEK293T cell line remains a valuable tool for experiments using CRISPR technology due to its high efficiency of transfection, enabling rapid and reliable genetic modifications for mechanistic studies [24]. Hence, we assessed whether sortilin or EGFR is required for mutual translocation into the nuclear fraction. Edited HEK293T cells, either lacking EGFR or SORT1, were transiently transfected with plasmids encoding wild-type EGFR (EGFRwt) or a mutant form (EGFR S229A) that impairs EGFR phosphorylation and nuclear importation [16] (Fig. 2h, j, k). We also transiently transfected a C-tail truncated version of sortilin (sortilin∆c) lacking its retrograde transport from membranes [23] (Fig. 2i–k). As previously evidenced above, EGF stimulation induced significant nuclear translocation of both EGFRwt and sortilin in control cells (Fig. 2g, j, k). In contrast, in HEK293T cells lacking EGFR (HEK CRISPREGFR), sortilin remained in the post-nuclear supernatant despite EGF stimulation (Fig. 2f). Likewise, in cells expressing the EGFR mutant S229A, known to inhibit EGFR nuclear translocation [16], sortilin failed to be translocated into the nucleus (Fig. 2h, J). Therefore, we expressed the sortilinΔc form in cells with a sortilin-null background (HEK CRISPRSORT1) and then stimulated them with EGF. We observed that the nuclear translocation of EGFR wt was unaltered, suggesting that EGFR can translocate to the nucleus independently of sortilin.

Fig. 2: EGFR promotes sortilin nuclear translocation.

a EGFR silencing by specific siRNA (SiEGFR) transfection for 72 h before assessment of sortilin importation into the nucleus by western blotting. b A549 with empty vector control (pLKO) and A549 shSORT1 cells were stimulated with EGF (+ EGF, 50 ng/mL) for 30 min or not (–) before subcellular fractionation. The nuclear extract (n) and post-nuclear supernatant (pns) were then subjected to western blotting with anti-EGFR, anti-sortilin, and antibodies directed against the cytoskeleton with anti-tubulin and the nucleus with anti-histone H3 to rule out cytoplasmic contamination in the nuclear fraction. c Relative optical density (ROD) of sortilin expression in isolated nuclei following EGFR depletion by siRNA. Histogram bars represent the relative optic density (ROD) of nuclear EGFR (d) or sortilin (e) normalized on histone H3 expression in fold of control in presence of EGF or not, following SORT1 depletion (ShSORT1). f–i HEK CRISPR cells for EGFR (HEK CRISPREGFR) were respectively transfected with empty vector (EV), EGFR wild type (EGFRwt) or mutant EGFR S229A (EGFRS229A) while CRISPR SORT1 cells (HEK CRISPRSORT1) were transfected with a C-tail truncated sortilin (sortilin∆c) mutant. Following 24 h of transfection and 30 min of EGF stimulation (+ EGF, 50 ng/mL) or not, control (–), we performed subcellular fractionation to isolated nucleus (n) from post-nuclear supernatant (pns). j–k Histogram bars represent the relative optic density (ROD) of nuclear EGFR or sortilin normalized on Lamin B expression in fold of control (respectively endogenous EGFR or sortilin) following different constructions upon EGF treatment (light blue bar) or not (dark blue bar). All values represent means ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001, ♦♦p<0.05, ♦♦p < 0.01, ♦♦♦p < 0.001 by Student’s t test. Each experiment was repeated at least three times.

Together, these findings indicate that sortilin did not mediate EGFR trafficking to the nucleus in response to EGF stimulation but likely plays a key role once it complexes with EGFR in the nucleus. Importantly, EGFR nuclear import seems to be required for sortilin translocation. Hence, aggregation of EGFR–sortilin complexes in the nuclei of EGF-stimulated cells suggests a specific sub-nuclear localization that might be involved in transcriptional functions [25].

EGFR–sortilin complexes co-immunoprecipitate with chromatin

To understand the role of nuclear EGFR–sortilin complexes in EGF-stimulated cells, we investigated their chromatin binding properties using ChIP assays combined with micrococcal nucleases (Mnase) digestion and release of mono-nucleosome (Supplementary Material 1a–d). Likewise, the specificity of anti-EGFR and anti-sortilin antibodies was assessed in HEK cells with knockout of either EGFR or SORT1 (supplementary fig. 1). Although sortilin has not been previously shown to act as a transcriptional co-factor, we hypothesized that its nuclear import could be mediated by its interaction with EGFR (Fig. 1i, j). Since the transcriptional pattern of nuclear EGFR is already known, we analyzed specific DNA sequences located within the EGFR promoter regions to determine whether sortilin might interact with and regulate these regions [26]. We selected two EGFR-targeted genes to evaluate the impact of sortilin interaction with EGFR promoter: cMYC, a key gene involved in epigenetic reprogramming [27], and CCDN1, a critical regulator of cell cycle progression [15]. ChIP assays using anti-EGFR or anti-sortilin antibodies showed that EGF stimulation resulted in the amplification of cMYC and CCND1 chromatin sequences (Fig. 3a). No amplification was observed following immunoprecipitation with the respective isotype controls (IgG1 ChIP EGFR and IgG ChIP sortilin), suggesting that both EGFR and sortilin interact specifically with chromatin and could participate in the regulation of EGF-induced genes (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3: EGFR and sortilin interact with chromatin.

a PCR amplification of CCND1 and cMYC promoter sequences in A549 cells stimulated with EGF (50 ng/mL) for 30 min following chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) with either anti-EGFR or anti-sortilin antibodies. Respective isotype IgGs, IgG1 ChIP (EGFR) and IgG ChIP (sortilin), were used as controls and compared with input samples (input chromatin), corresponding to non-ChIP DNA, as an internal control. b Peaks enriched for EGFR and sortilin in A549 cells stimulated with EGF (50 ng/mL) for 30 min. TTS Transcription Termination Site, TSS Transcription Starting Site, CDS Coding Sequence, UTR Untranslated Region (c) Distribution of EGFR and sortilin ChIP-Seq reads near 5 kb upstream/downstream of TSS. d ChiP-Seq overview with IGV genome browser showing peaks of DNA-binding pattern of EGFR and sortilin on CCND1 and cMYC TSS. e Nucleotides motifs enriched in DNA-binding sequences from EGFR or sortilin immunoprecipitated peaks.

To identify the DNA regions immunoprecipitated by anti-EGFR and anti-sortilin antibodies, the ChIP products were sequenced (ChIP-Seq). All libraries bound by these antibodies met all ChIP-Seq quality control criteria (Supplementary Materials 1b, c). ChIP-Seq experiments were performed on biological replicates following stimulation with 50 ng/mL EGF for 30 min, with reads averaging 50 million. In stimulated A549 cells, the peaks are predominantly enriched and distributed within intergenic and intronic regions, as well as toward transcriptional regulating elements, including the TSS and the transcription termination site (TTS) (Fig. 3b). Analysis of the segmentation of TSS sequences revealed a preferential distribution for EGFR and sortilin. ChIP-Seq peak distributions within 5 kb of TSS with aggregation plots showed that the TSS/TTS ratios for EGFR and sortilin were 2.44 and 1.78, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2). Not surprisingly, we observed an abundance of TSS peaks co-occurring with the highest expression of EGFR (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 2). Likewise, their overlap positions in close proximity to the TSS region suggested that EGFR–sortilin complexes affected gene activity (Supplementary Fig. 2). The PLA and co-immunoprecipitation assays showing the physical interactions between EGFR and sortilin in the nuclei of A549 cells (Fig. 1a–c, i, j) suggested that EGFR and sortilin have common binding sites on target loci. Significant correlations between EGFR and sortilin profiles were shown on ChiP-Seq overview using the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) genome browser [28], which found EGFR and sortilin binding sites on the CCND1 and cMYC TSS (Fig. 3d). Similarly, in silico analysis suggested that both EGFR and sortilin bound to an AT-rich minimal consensus sequence (ATRS), consisting of TNTTT or TTTNT, with N being any nucleotide (Fig. 3e). These genomic sequences were previously associated with the EGFR chromatin binding site [15, 26], suggesting that EGFR–sortilin complexes potentially bind chromatin through EGFR. However, these results cannot exclude that sortilin may bind chromatin itself in the region of the ATRS sequences.

Taken together with our previous results, the binding patterns of EGFR and sortilin were close to gene-proximal regulatory elements, particularly those associated with EGF-induced molecular processes. The proximity of these complexes to key transcriptional regions, such as the TSS, and their potential to bind to ATRS sequences, indicate that EGFR–sortilin complexes likely play an important role in regulating the transcription of EGF-responsive genes, such as cMYC and CCND1.

EGF stimulation enhances sortilin DNA binding

To further assess whether EGF promotes EGFR and sortilin DNA binding to transcriptional regulatory elements, we designed primers corresponding to the TSS regions of genes derived from gene ontology (GO) analysis (Supplementary Table 4), followed by the use of immunoprecipitated chromatin as a qPCR template. A549 cells were respectively depleted for EGFR (Fig. 4a) and SORT1 (Fig. 4b) mRNAs [18, 19] using specific lentivirus delivering shRNAs. Then, depleted cells were incubated with antibodies to specifically immunoprecipitate chromatin. EGF stimulation triggered significant (p < 0.001) chromatin binding of EGFR onto the TSS regions derived from CCND1, cMYC, and several genes selected by GO analysis (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 3a). EGF stimulation significantly enhanced sortilin binding to the TSS of selected genes (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 3b). On the contrary, its binding to cMYC TSS was decreased following EGF stimulation compared with control cells (Fig. 4b). Thus, we assessed mRNA level of SORT1, EGFR, CCND1 and cMYC, 30 or 60 min of EGF stimulation (Fig. 4c). Following 60 min of EGF stimulation both EGFR and CCND1 mRNA level increased significantly (p < 0.05) whereas cMYC mRNA level increased more slowly to reach its basal level. Conversely, SORT1 mRNA levels remain sensitive to EGFR transcriptional program following EGF stimulation [29]. Since both SORT1 mRNA level and its binding to cMYC TSS decreased, these results would suggest that sortilin is involved in cMYC gene inhibition. Hence, we assessed whether sortilin or EGFR binds the chromatin. Interestingly, by using either sortilin or EGFR-depleted cell lines, EGF stimulation triggers an increase of EGFR and sortilin binding to CCND1 TSS, respectively, in SORT1 and EGFR-depleted cell lines (Fig. 4d, e). In addition, their binding to cMYC TSS decreased, suggesting that EGFR–sortilin complexes would be required especially for cMYC gene activity. However, EGFR depletion notably decreased cMYC mRNA levels (p < 0.001), whereas SORT1 depletion led to a significant increase in the mRNA levels of both EGFR, cMYC and CCND1 (p < 0.001). These results suggest that sortilin plays a role in the transcriptional regulation of these genes, likely by limiting EGFR transcriptional activity (Fig. 4f). These results suggest that sortilin binding in normal cells by competing with EGFR potentially limits cMYC and CCDN1 gene activity. Consequently, these findings indicate that changes in cMYC expression could depend on EGFR (activating) and sortilin (inhibiting) levels, confirming their antagonistic and competitive roles in regulating cMYC mRNA expression.

Fig. 4: EGF stimulation increases EGFR and sortilin binding to chromatin.

a, b Quantitative PCR (qPCR) of chromatin immunoprecipitated (ChIP) by anti-EGFR or anti-sortilin antibodies in empty vector control cells (pLKO) and cells depleted respectively for EGFR or SORT1 mRNA (shRNAs), and incubated in the absence or presence of EGF (50 ng/mL) for 30 min. Histograms represented the percentages of input following normalization. CCND1 and cMYC promoters were amplified by qPCR. c mRNA level (fold of control: EGF non-stimulated cells) of SORT1, EGFR, CCDN1 and MYC in A549 cells following 30 (dark blue histogram) and 60 min (light blue histogram) of EGF stimulation (50 ng/mL). d, e Results of EGFR and sortilin ChIP-qPCR of A549 cells depleted or not, either for SORT1 (ShSORT1) or EGFR (ShEGFR), incubated in the presence of EGF (50 ng/mL for 30 min). CCND1 and cMYC promoter sequences were amplified by qPCR. f mRNA level (fold of control: EGF non-stimulated cells) of SORT1 (dark blue histogram), EGFR (light blue histogram), CCDN1 (gray histogram) and cMYC (white histogram) in A549 cells following 30 min of EGF stimulation (50 ng/mL).

Taken together, these findings suggest that sortilin acts as an inhibitor of EGFR-driven gene activation, particularly for cMYC, by limiting the transcriptional activity of EGFR and acting as a nuclear antagonist. In this capacity, sortilin likely plays a tumor suppressor-like role in LUAD by modulating the transcriptional network activated by EGFR, thereby controlling the expression of key oncogenic drivers.

Sortilin overexpression limits polymerase II recruitment to TSS

Hence, to evaluate whether changes in sortilin expression could be involved in EGFR transcriptional activity, we performed ChIP experiments using H1975 cells. This cell line harbors the EGFR T790M mutation, particularly suitable for studying the effects of EGFR inhibitors like osimertinib. However, this cell line harbors the weaker expression of sortilin and thereby offers the possibility to overexpress SORT1 (OE-SORT1) and study the specific impact of EGFR T790M mutation on EGFR and sortilin dynamics in comparison to control cells with control empty vector (EV). As expected, EGF stimulation of control (EV) cells triggered significant (p < 0.001) chromatin binding by both EGFR and endogenous sortilin (Fig. 5a, b and Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). By contrast, sortilin overexpression significantly reduced EGFR DNA binding on CCND1 and cMYC despite EGF stimulation (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 4a). Under such experimental conditions in H1975 cells, EGFR chromatin binding to CCND1 and cMYC TSS was reduced in comparison to EGF-stimulated cells. By contrast, sortilin binding to the cMYC TSS is slightly increased by EGF stimulation (Fig. 5b). Sortilin binding to the cMYC and CCND1 TSS was increased in SORT1-overexpressing cells compared to empty vector control (EV) cells. Thus, sortilin continued to occupy the cMYC TSS when compared with non-stimulated OE-SORT1 cells (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 4b). Using this model, we assessed the recruitment of polymerase II (Pol II), belonging to the initiating transcription complex. Interestingly, the chromatin binding of Pol II to cMYC and CCND1 TSS was significantly lower in cells overexpressing sortilin than in control cells, as was the binding of Pol II to selected genes from GO analysis (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 4c). These results suggest that sortilin might impair the recruitment of Pol II, thereby influencing CCND1 and cMYC expression. Hence, to further evaluate the consequences of increased sortilin chromatin binding, we measured the levels in these cells of CCND1 and cMYC mRNAs. Surprisingly, sortilin overexpression significantly reduced (p < 0.001) the mRNA levels of the EGFR co-drivers CCND1 and cMYC (Fig. 5d).

Fig. 5: Sortilin overexpression increases sortilin chromatin binding on cMYC and CCND1 and limits polymerase II recruitment.

a, b EGFR and sortilin ChIP-qPCR were performed on H1975 control cells transfected with control empty vector (EV) or on H1975 sortilin overexpressing cells (OE-SORT1) in the absence or presence of EGF (50 ng/mL) for 30 min. CCND1 and cMYC promoters were amplified by qPCR. c Pol II ChIP-qPCR performed on EV and OE-SORT1 cells. d Levels of CCND1 and cMYC mRNAs in control empty vector (EV) and OE-SORT1 cells by qPCR. All values represent means ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 and ###p < 0.001 by Student’s t test. Each experiment was repeated at least three times.

Taken together, these results suggest that the amount of sortilin would represent a limiting factor to impair EGFR chromatin binding and Pol II recruitment at the TSS of EGF response genes.

Osimertinib triggers nuclear importation of EGFR

Given the link between EGFR nuclear translocation and TKI resistance [9, 16, 30], we studied sortilin function in TKI-treated H1975 cells with EGFR T790M mutations and extended our analysis to H3255 cells harboring an L858R activating mutation. EGFR’s spatial and temporal distribution impacts relapse risks due to sustained signaling or enhanced nuclear importation. Notably, EGFR subcellular distribution varies depending on its mutational status; for instance, in H1975 cells harboring both the L858R and T790M mutations, EGFR is constitutively active and undergoes internalization even in the absence of ligand stimulation [18, 31]. We investigated whether osimertinib exposure, a TKI targeting the EGFR T790M mutation or the L858R mutation indirectly, affects EGFR chromatin binding in these two models. Likewise, we assess whether the anti-cancer properties of this TKI are limited by the competition between EGFR and sortilin for chromatin binding.

As attempted, 24 h of osimertinib treatment triggers a significant decrease in EGFR phosphorylation at concentrations as low as 0.01 µM for both cell lines (Fig. 6a, b) and suppresses AKT and ERK phosphorylation (fold of control) in the presence or absence of EGF stimulation in both cell lines (Fig. 6a, b). Notably, a complete inhibition of EGFR phosphorylation was observed at 1 µM osimertinib in the H1975 cell line, which was the effect we sought to achieve in this model. Consistent with these findings, a clear dose-dependent inhibition of EGFR phosphorylation was illustrated (Supplementary Fig. 5a–d) and a marked reduction in cell viability, particularly upon sortilin overexpression induced by doxycycline in both cell lines (Supplementary method 1 and Supplementary Fig. 5e, g). To mimic physiological conditions, we used EGF stimulation since EGF binding can promote receptor internalization [32]. Our results also confirm that EGF stimulation induces a decrease of L858R and L858R/T790M mutated EGFR in H3255 and H1975 cell lines, as already described [33] (Fig. 6a, b). Additionally, osimertinib treatment led to a marked reduction in cyclin D1 expression, further supporting the suppression of key signaling pathways associated with cell proliferation. Strikingly, while the T790M mutant EGFR remains internalized under control conditions (Fig. 6c, insets 1.1, 1.2 and 3.1, 3.2), we found that treating H1975 and H3255 cells with 1 µM osimertinib for 24 h triggered EGFR subcellular relocation toward the nuclei of exposed cells (Fig. 6c, insets 2.1, 2.2 and 4.1, 4.2). Cell fractionation and isolation of nuclei confirmed a significant importation of EGFR into the nuclei (Fig. 6d, e), despite a reduction in its kinase activity, as evidenced by decreased phosphorylation levels (P-EGFR) (Fig. 6a, b). Importantly, under these conditions of complete EGFR phosphorylation inhibition, the phenotypic and transcriptional effects we observed can be attributed specifically to EGFR inhibition rather than off-target actions (Fig. 6a, b and Supplementary Fig. 5a–d).

Fig. 6: Osimertinib enhances nuclear importation of EGFR.

a Western blot analysis of phospho-EGFR, total EGFR, phospho-AKT, total AKT, phospho-ERK, total ERK, sortilin, MYC and cyclin D1 in H1975 and H3255 cells in the absence or presence of EGF (50 ng/mL) for 30 min, treated or not with osimertinib (1 μM) for 24 h. Actin serves as a loading control. b Densitometric quantification in relative optical density (ROD) of p-EGFR/total EGFR, p-AKT/total AKT, and p-ERK/total ERK ratios, normalized to untreated controls (fold of control, indicated by dotted line). All values represent means ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, by Student’s t test. Each experiment was repeated at least three times. c EGFR localization was analyzed by confocal microscopy in H1975 and H3255 cells, in the absence or presence of osimertinib treatment (1 µM for 24 h). Scale bar, 10 μm yellow arrows show EGFR localization. d Western blotting performed on nuclear fraction showing that treatment of H1975 and H3255 cells with osimertinib (1 µM for 24 h) triggers EGFR and sortilin importation into cell nuclei. Lamin B was used as a loading control for the nuclear fraction. Molecular weight (MW) in kilodaltons (kDa). e Densitometric quantification in relative optical density (ROD) of total EGFR, and sortilin, normalized to untreated controls (fold of control). All values represent means ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, by Student’s t test. Each experiment was repeated at least three times.

Then, we subsequently assessed whether EGFR binding to chromatin increases following its enrichment in the nuclear compartment. ChIP EGFR in H1975 and H3255 cells showed that only cMYC TSS binding was significantly increased following osimertinib treatment in both cell lines (Fig. 7a, c and Supplementary Fig. 6a). Strikingly, under the same conditions, ChIP analysis of sortilin revealed that osimertinib treatment significantly increased the binding of sortilin to CCND1, cMYC, and selected genes identified from GO analysis in H1975 whereas only cMYC TSS binding was significantly increased in H3255 cells. (Fig. 7b, d and Supplementary Fig. 6b). To further analyze gene activity following chromatin binding by EGFR and sortilin, we assessed the levels of CCND1 and cMYC mRNAs in these cells (Fig. 7e, f). Osimertinib treatment of H1975 cells did not significantly reduce the level of cMYC mRNA relative to that of CCND1 mRNA (Fig. 7e), whereas both transcripts decreased in the H3255 cells (Fig. 7f). However, when H1975 cells overexpress SORT1 (OE-SORT1), we observed that osimertinib induced a significant decrease in cMYC mRNA level in comparison to control EV cells (Fig. 7g). These results would suggest that the mutational status of NSCLC cell lines might influence the regulation of cMYC. Furthermore, while no significant variation was observed in cMYC protein expression, Cyclin D1 protein levels were strongly decreased in the presence of osimertinib alone in both H1975 and H3255 cell lines. This decrease in Cyclin D1 occurred concurrently with the inactivation of EGFR, AKT and ERK phosphorylation (Fig. 6a, b).

Fig. 7: Osimertinib modulates EGFR and sortilin chromatin binding.

a–d Quantitative PCR (qPCR) of chromatin immunoprecipitated (ChIP) by anti-EGFR or anti-sortilin antibodies in H1975 and H3255 cells incubated in the absence or presence of EGF (50 ng/mL) for 30 min or osimertinib (1 µM) for 24 h. Histograms represented the percentages of input following normalization. CCND1 and cMYC promoters were amplified by qPCR. e, f mRNA level (fold of control: osimertinib non-treated cells) of CCDN1 and MYC in H1975 and H3255 cells following osimertinib treatment (1 µM) for 24 h. g mRNA level (fold of control: osimertinib non-treated cells) of CCDN1 and MYC in control H1975 cells carrying empty vector (EV) and H1975 cells overexpressing (OE-SORT1) in the presence of osimertinib (1 µM for 24 h). All values represent means ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 and ###p < 0.001 by Student’s t test. Each experiment was repeated at least three times.

Taken together, these results indicate that EGFR and sortilin compete for binding to the regulatory elements of the cMYC gene, and that the nuclear expression of sortilin may be a limiting factor in counteracting the transcriptional program driven by EGFR.

Inverse correlation between cMYC and sortilin expression

Because uncontrolled EGFR signaling leads to cell transformation [3, 34] and LUAD initiation [35,36,37], we developed a Tet-ON inducible model to trigger sortilin expression in H1975 cells. Doxycycline (Dox) treatment increased sortilin expression and slightly decreased EGFR (Fig. 8a). EGFR immunoprecipitation showed increased EGFR–sortilin complexes in nuclei of induced cells, with or without EGF stimulation (Fig. 8b). Interestingly, levels of CCND1 and cMYC mRNAs decreased significantly following Dox stimulation (p < 0.001, Fig. 8c). In vivo, Dox-treated mice with induced tumors showed significantly slower tumor progression (p < 0.001, Fig. 8d) and reduced CCND1 (p < 0.01) and cMYC (p < 0.05) mRNAs (Fig. 8e). These results suggest that sortilin may repress EGFR-regulated genes upon EGF stimulation. Analyzing SORT1 mRNA expression in 54 LUAD tumors, obtained from the Tumor Bank (CRBiolim) of Limoges University Hospital, under protocols approved by the IRB (AC-2013-1853, DC-2011-1264), we found significantly lower levels in tumors compared to normal tissue (p < 0.001, Fig. 8f). This finding was confirmed in two other studies [38, 39] (p < 0.001, Fig. 8g, h), regardless of disease stage (Fig. 8i). By sorting patients by SORT1 mRNA quartiles, we observed that only cMYC mRNA expression significantly decreased in the highest quartiles of SORT1 mRNA (p < 0.001, Fig. 8j, k). We evaluated sortilin effect on cMYC expression in MSKCC cBioPortal data sets [40, 41], including 240 TCGA patients (Fig. 8l) [42] and 665 CCLE cancer cell lines (Fig. 8m) [43]. cMYC expression was inversely correlated with SORT1 in both patient tissues (r = –0.24, p = 8.7e-8) and cell lines (r = –0.2, p = 1.6e-8) while no such correlation between SORT1 mRNA and CCND1 mRNA was observed.

Fig. 8: cMYC expression correlates inversely with SORT1 expression in vitro and in tumor samples.

a Western blotting showing EGFR and sortilin expression in lysates of H1975Tet-ON-SORT1 cells following incubation in the absence or presence of 100 nM doxycyclin (dox) for 24 h. b Anti-EGFR immunoprecipitation (IP) of isolated nuclei from H1975Tet-ON-SORT1 cells following incubation in the absence or presence of 100 nM doxycyclin for 24 h and stimulation with 50 ng/mL EGF for 30 min and immunoblotting (IB) with anti-sortilin. c Comparison of CCND1 and cMYC mRNA levels in H1975Tet-ON-SORT1 cells following incubation in the absence or presence of 100 nM doxycycline for 24 h. d Effects of doxycycline on tumor induction by H1975Tet-ON-SORT1 cells in NOD-SCID mice. H1975Tet-ON-SORT1 cells were subcutaneously engrafted (3 × 106 cells/mouse) onto NOD-SCID mice. Fifteen days later, corresponding to the beginning of tumor development, mice were treated with 2 mg/mL doxycycline in drinking water or drinking water alone, and tumor volumes were measured. Tumor growth curves are shown for mice treated with dox (light blue curve) and for control mice (blue curve). e qPCR measurements of expression of CCND1 and cMYC mRNAs in tumors of mice treated with (light blue bar) or without (dark blue bar) dox. Measurements of SORT1 mRNA levels (Z-score) in normal and lung adenocarcinoma (ADC) tissue samples obtained from the (f) Limoges University Hospital cohort and data sets from g Hou et al. and h Salamat et al. (i) qPCR measurements of SORT1 mRNA levels in tumor samples compared to healthy tissues from the Limoges University Hospital cohort at different stages. Quantification of (j) CCND1 and k cMYC mRNA levels in tumor samples from the Limoges University Hospital cohort expressing the lowest and highest quartiles of sortilin expression. l Correlation between levels of cMYC and SORT1 mRNA levels in NSCLC patients in the TCGA database (r = –0.24; p = 8.7.10–8) and m in solid cancer cell lines from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) database (r = -0.2; p = 1.6.10–8). Diagrams represent the correlation between SORT1 expression and cMYC expression. All values are expressed as means ± SD, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 by Student’s t test, n.s. not significant. Each experiment was repeated at least three times. n Representative immunohistochemical staining of sortilin and cMYC in lung tumor samples from the lower and upper quartiles of SORT1 mRNA expression. Scale bars represent 200 μm.

Immunohistochemical analysis of cMYC expression was performed on lung tumor samples stratified into the lower and upper quartiles of sortilin expression. We observed a significant inverse correlation between sortilin and cMYC expression levels. Tumors with low sortilin expression exhibited high cMYC immunoreactivity (Fig. 8n, insets 1.1 to 1.3, and 3.1 to 3.3), whereas tumors with high sortilin expression related to the upper quartile showed low cMYC staining intensity (Fig. 8n, insets 2.1 to 2.3 and 4.1 to 4.2).

These findings suggest that sortilin impairs EGFR-regulated cMYC transcription. Likewise, in lung malignant tissues, sortilin is often downregulated, which disrupts its normal tumor-suppressive function of limiting EGFR transcriptional responses. This loss of sortilin-mediated regulation potentially enhances tumor malignancy, particularly in the context of mutant EGFR, and may contribute to reduced efficacy of TKI treatment.